A BIT OF A PREAMBLE.

Why photogravure invites interpretation instead of asserting truth.

In a time when images are everywhere - instant, sharp, and endlessly repeatable - what does it mean to make an image that quietly invites attention?

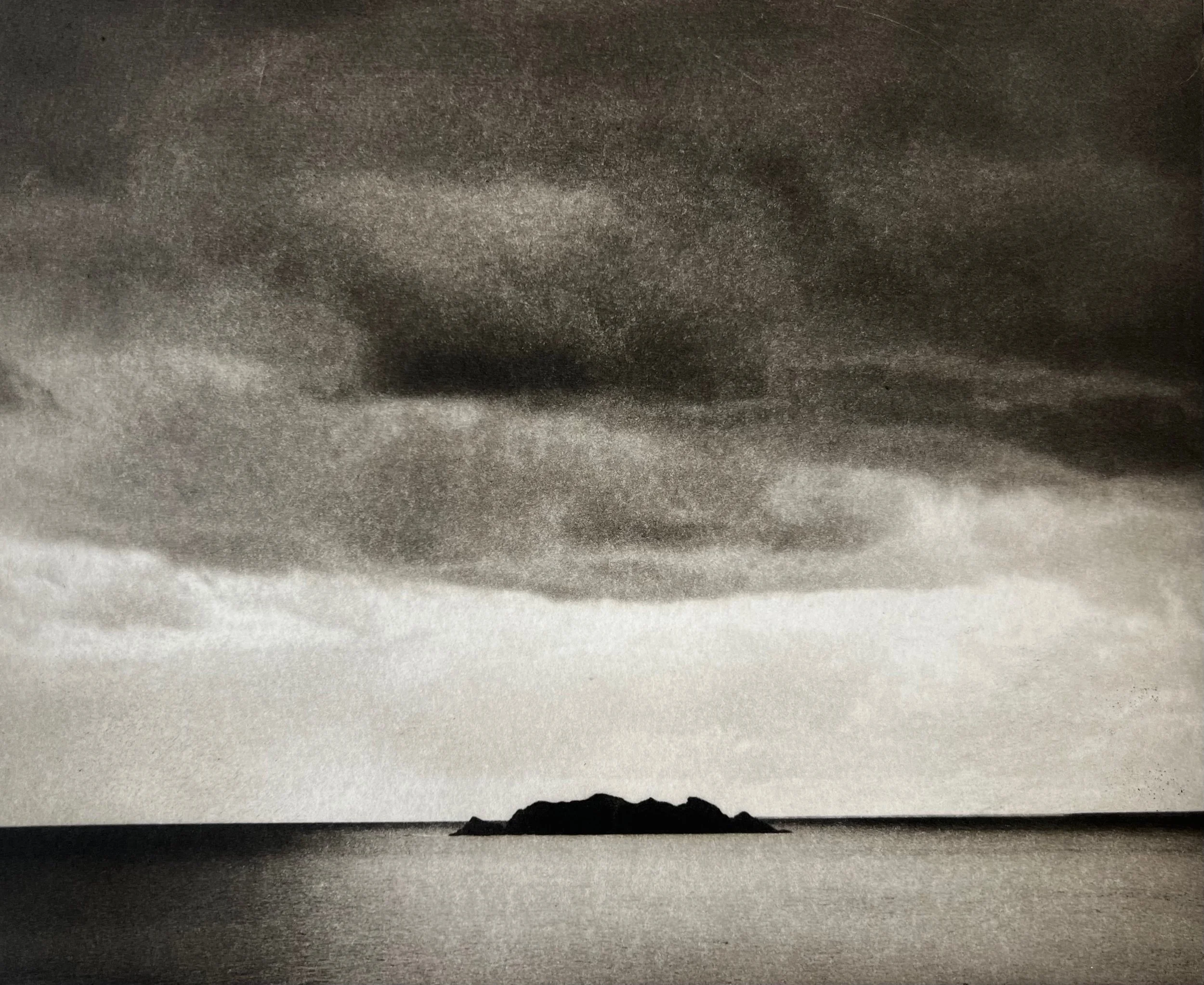

Photogravure doesn’t demand to be seen. It doesn’t shout its meaning. It’s an echo rather than a declaration. The viewer is invited not to decode or react, but to dwell - to sit with the image and allow it to unfold in time.

This is the beginning of a collection of notes on photogravure. Not as a process guide or a historical timeline, but as a conversation about what it feels like to make and experience these prints. About what this medium allows, and why that is of interest to me.

Photogravure occupies a unique space. Between photography and printmaking. It’s photography, yes, but softened and filtered through a tactile, handmade process. It doesn’t live in the same world as high-gloss digital photos or the cold, surgical sharpness of inkjet prints.

It’s something slower. Something quieter.

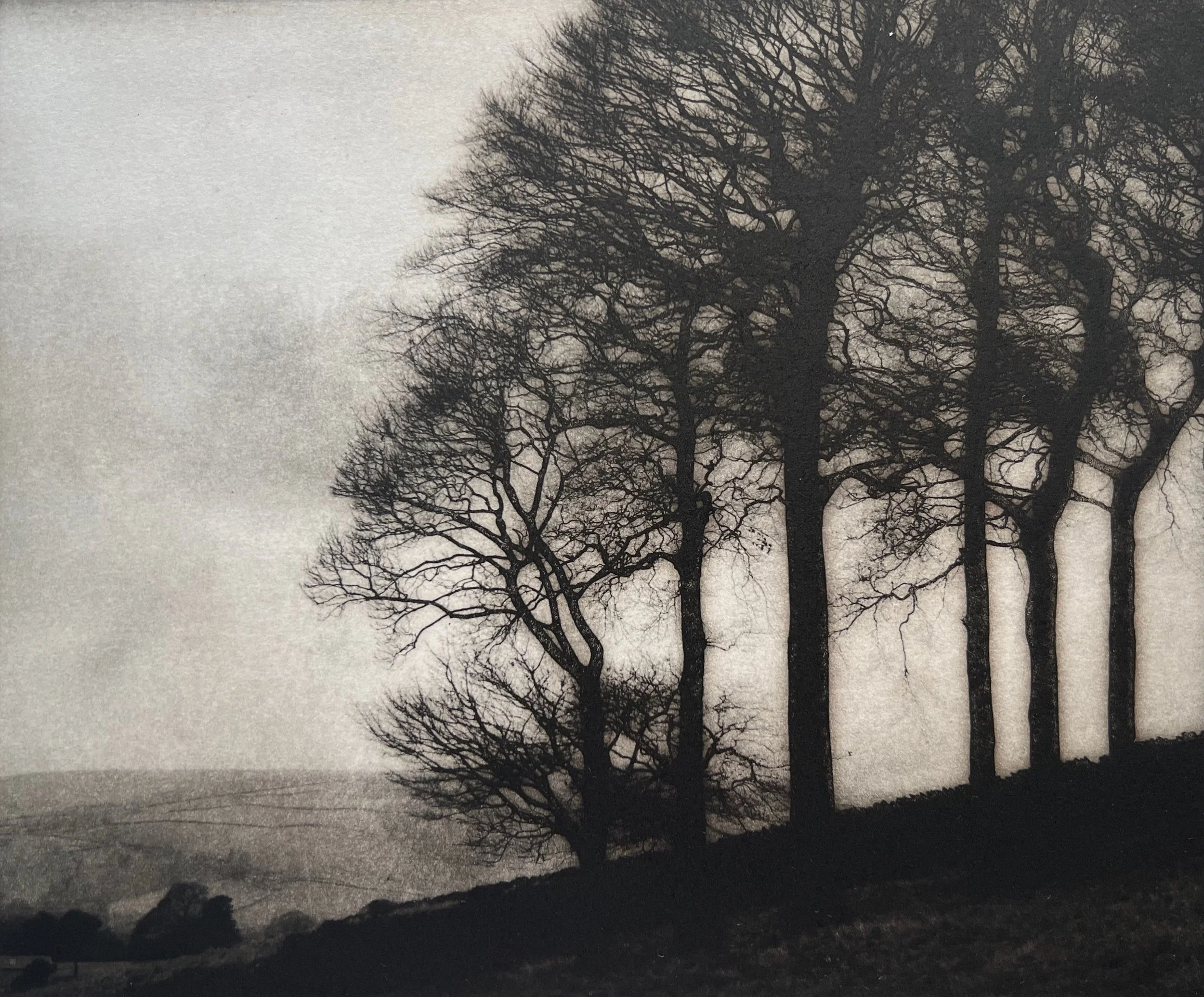

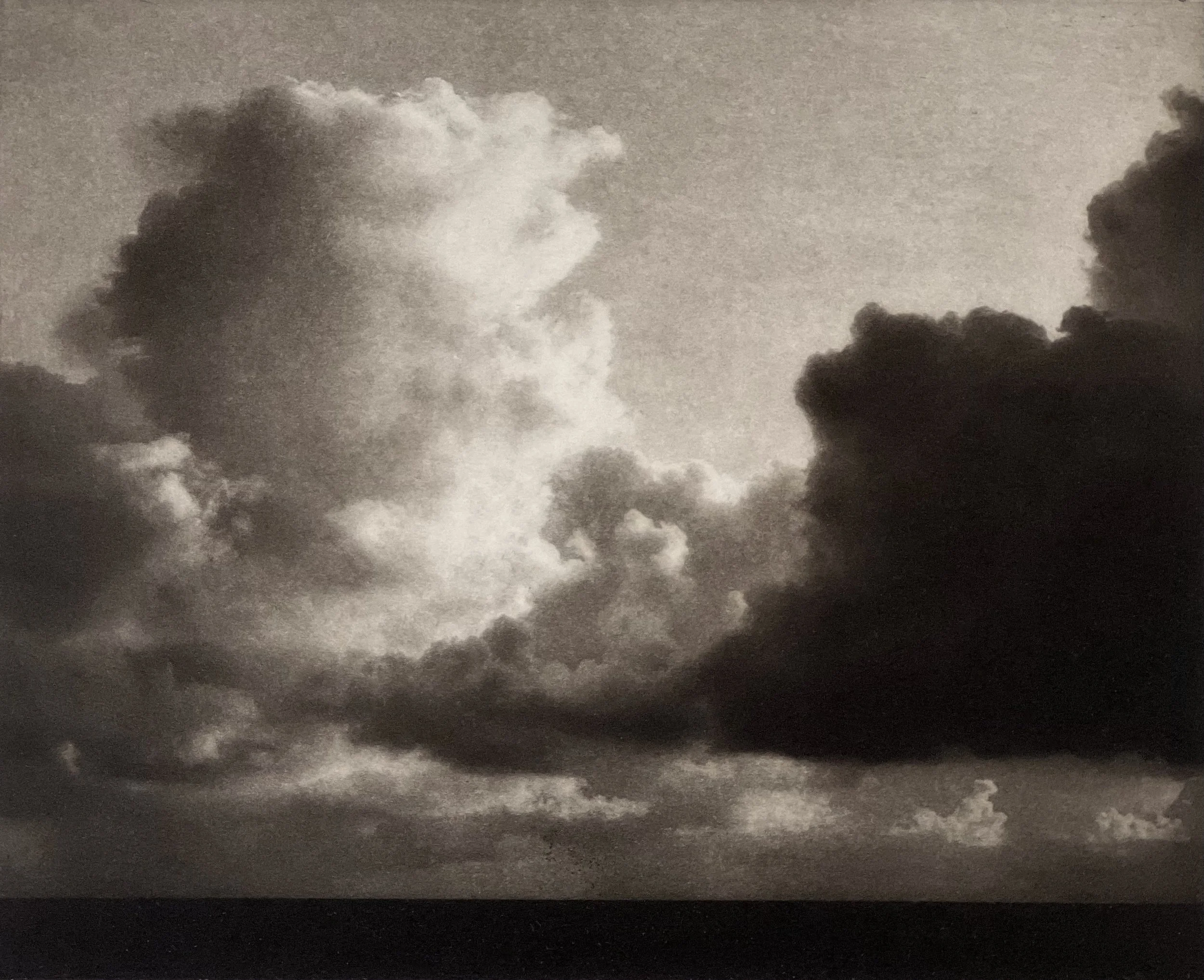

The process itself encourages interpretation. The image, once precise, begins to dissolve: softened by the grain of an aquatint screen, warmed by the ink, held in the gentle pressure of the press. By the time a photogravure print emerges, it’s no longer a document - it’s an invitation. Less about what happened, more about how it felt.

In that sense, photogravure resists the expectations of photography as evidence. It favours the visually poetic over the factual. The suggestive over the explicit. The hand, the gesture, the imperfection - these become integral to the process, not incidental.

This series of notes explores how photogravure blurs boundaries: between photograph and print, craft and concept, past and present. And how its ambiguity isn’t a flaw - but the point.

If you’ve ever stood before a print and felt something you couldn’t quite name - something soft, slow, and deep - you’ve already felt what photogravure can do.

Digital Sharpness vs. Handmade Softness

How the Medium’s Materiality Sets It Apart in a World of Perfect Pixels

How the medium’s materiality sets it apart in a world of perfect pixels:

In an era of retina displays, megapixels and 4K everything, photogravure steps quietly in the opposite direction. It doesn’t try to keep up. It doesn’t compete. Instead, it invites us into a different sensory world - one defined not by resolution, but by resonance.

Photogravure's materiality - the plate, the ink, the paper, the press - introduces a softness that is not a flaw but a feature. This softness isn't blur. It’s a quality of presence. Tactile, tonal, and subtly uneven in a way that feels distinctly human.

Digital sharpness as default:

Digital photography privileges clarity. In many ways, it’s designed to remove the interference of medium. Noise reduction, lens correction, sharpening algorithms - all engineered to deliver an image that feels frictionless, untouched by process. We’re trained to read this precision as professionalism.

Intentional softness:

Photogravure introduces nuance through its very construction. The etched plate doesn’t simply reproduce an image - it interprets it. The handmade softness that results isn't nostalgic or lo-fi. It’s interpretive. A form of translation.

The ink soaks differently into handmade paper than machine-cut fiber. The press leaves a gentle emboss. The grain of the aquatint subtly shifts across tonal regions. Every layer - physical and perceptual - adds atmosphere, not noise.

The subtlety of the handmade:

In photogravure, this process is not invisible. It reminds the viewer that this image has been touched. Not just by light and lens, but by hands.

When people stand in front of a photogravure print, they lean in. There’s nothing flat-screen about it. The softness draws them closer. It invites not just looking, but lingering.

As images become more ubiquitous, more optimized, more same, the subtlety of the handmade matters more. Photogravure isn’t trying to replicate the digital - it’s offering a counterpoint. A chance to feel something beyond pixels.

The Liminality of Photogravure

It all begins with an idea.

Photogravure lives in an in-between space - part mechanical, part craft.

What makes this in-between so powerful and how does it shape the viewer’s emotional response?

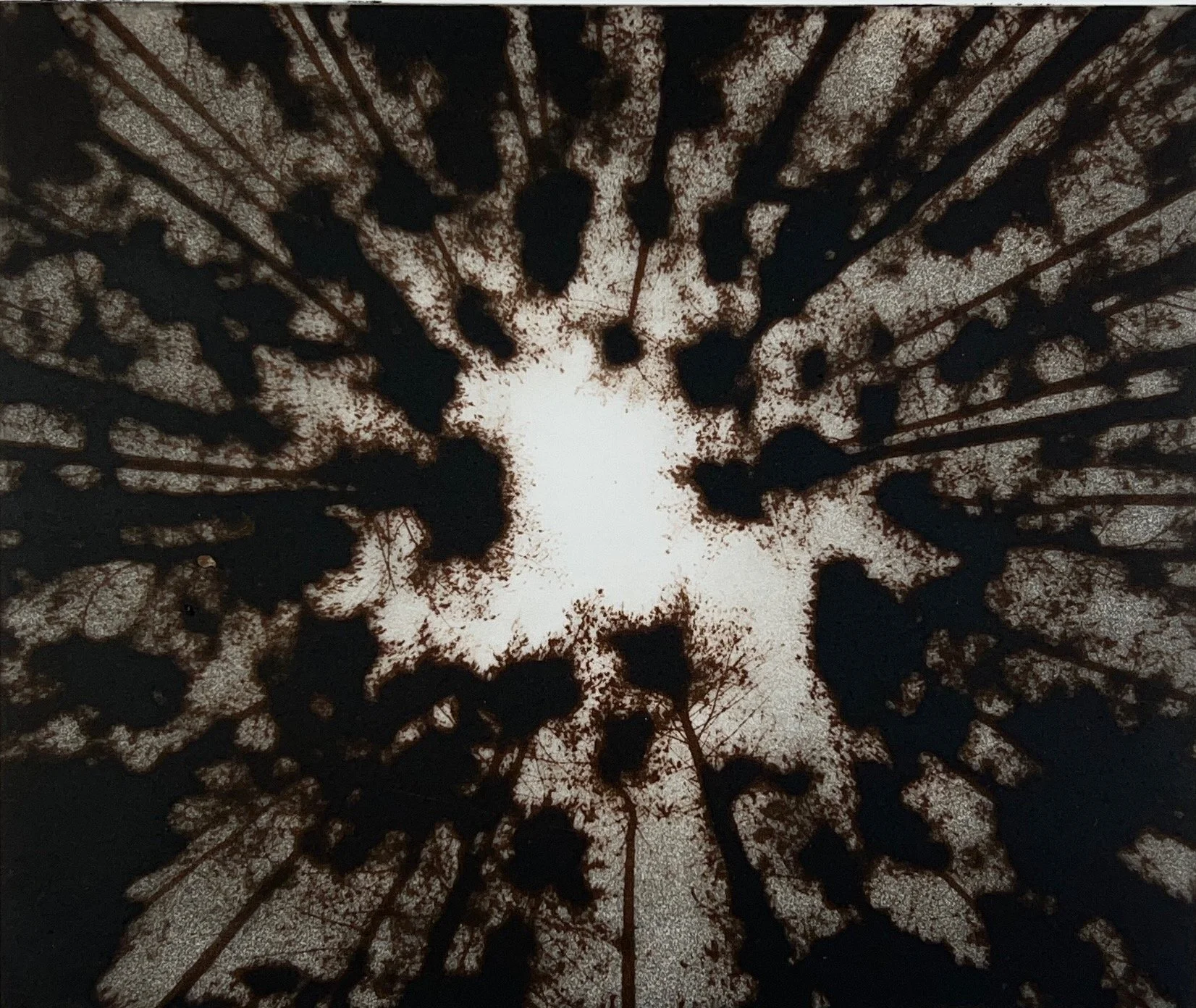

Photogravure is not quite a photograph. It isn’t a traditional print either. It’s an image suspended between worlds - etched but photographic, reproducible but unique, physical and yet quietly ethereal.

In a world that favours clearly defined categories, photogravure resists classification. That resistance unsettles the eye just enough to slow us down, to ask: What am I looking at? That pause, that slight disorientation, is part of the experience.

The beauty of betweenness:

Liminality has always had power. It’s the moment before a threshold is crossed. Photogravure inhabits that kind of space. It blurs the boundaries between disciplines. It’s a process that quietly reclaims the tension between precision and imperfection.

Where modern photography is often immediate and printmaking is often interpretive, photogravure lives in this visually poetic overlap.

Emotion in ambiguity

Because photogravure straddles these edges, it creates emotional ambiguity. It feels familiar but strange, precise but soft, historical yet current. That emotional tension gives it depth. It bypasses the literal and goes somewhere more atmospheric, more internal.

The mind doesn’t quite settle. And that’s the point.

There’s something moving about that unsettled quality - an image that feels almost photographic, nearly printed, and somehow more than both. The viewer feels it, even if they can’t articulate why.

The process of making a photogravure mirrors this in-betweenness. It’s a collaboration between digital and analogue, science and touch, ink and light. The maker acts as translator between these worlds. It’s not a mechanical transfer; it’s a transformation. That process leaves traces. The final image carries the residue of its passage through the different states of the creative process.

Unfixing the Index: The Hand in the Image

It all begins with an idea.

Photography is often tied to truth. But what happens when we smudge, ink, and press that truth by hand? This post considers photogravure’s indexical roots - and how it transcends them.

The indexical inheritance

Roland Barthes argued that the photograph is an index - a physical trace of a moment that once existed. Light bounces off a subject, hits a photosensitive surface, and creates a mark. The photograph, in this view, is a wound left by time, a scar of the real. It says, this happened.

But what happens when that trace is reinterpreted by hand?

Photogravure begins with that same indexical logic: a photographic image is captured and etched into a plate. But then the image passes through ink, hand-wiping, paper, and pressure. What was once a strict imprint of light, becomes something more layered, more ambiguous - more human.

Inking a plate isn’t mechanical. It’s intimate. The hand alters tone, emphasis, texture. No two prints are exactly alike. The original truth of the photographic index becomes flexible, suggestive - even poetic. It’s still rooted in a real moment, but it no longer claims to be neutral.

The human touch introduces intention. Mood. Even memory.

This is where photogravure parts ways with photography. It carries the index in its DNA, but doesn’t serve it blindly. It pushes against it, smudges it, complicates it. The print is not a window—it’s a veil. What you see is filtered through labour, material, and the alchemy of touch.

From evidence to essence:

Photogravure doesn’t just show that something existed. It shows how that existence feels. It moves from that physical imprint of reality to a visual essence.

There’s a kind of grace in that shift.

We’re no longer looking at a frozen moment. We’re looking at a moment passed through time, tools, and transformation. The image is still indexical - but it’s also expressive. It contains both a trace and a translation.

What began as a visual fact becomes a visual feeling.

Interpretation Over Reproduction

It all begins with an idea.

Photogravure isn’t about replication - it’s about resonance.

Photogravure as a medium prioritises emotional truth over objective documentation and that opens a space for deeper engagement.

In a world saturated with digital images - each one sharp, colour-corrected, and endlessly replicable - it’s easy to forget that art doesn’t need to be accurate.

Photogravure resists this compulsion. It doesn't aim to reproduce an image perfectly. Instead, it invites interpretation. The plate is inked by hand. The tones shift slightly from print to print. The process introduces texture, warmth, irregularity.

Where most photography promises fidelity, photogravure delivers a feeling.

The maker as interpreter:

Every step in the photogravure process is a moment of choice.

How dark or light should the positive acetate be? what settings to use on the UV exposure unit? What colour ink to used? How much ink stays on the plate? How heavily is it wiped? What paper will carry the image? These decisions aren’t incidental - they're interpretive. The artist isn’t just reproducing an image; they’re engaging with it, translating it, responding to it.

The result isn’t a carbon copy. It’s a conversation between image and maker. A visual echo of something remembered more than recorded.

This is where the medium’s emotional charge lives - not in what is shown, but in how it’s shown.

Resonance trumps resolution:

Photogravure slows the image down. It resists the speed and sameness of modern visual culture. That slowness is an invitation to look longer, to feel more deeply. It creates space for ambiguity, softness, nuance.

And when an image resonates, it lingers. Not because it is exact, but because it means something.

A MEMORY VERSUS A MOMMENT

photogravure feels more like a memory than a moment.

Why photogravure feels more like a memory than a moment.

If digital photos freeze time, photogravure frees it.

The medium of photogravure distils experience into feeling, becoming more about memory than the moment itself.

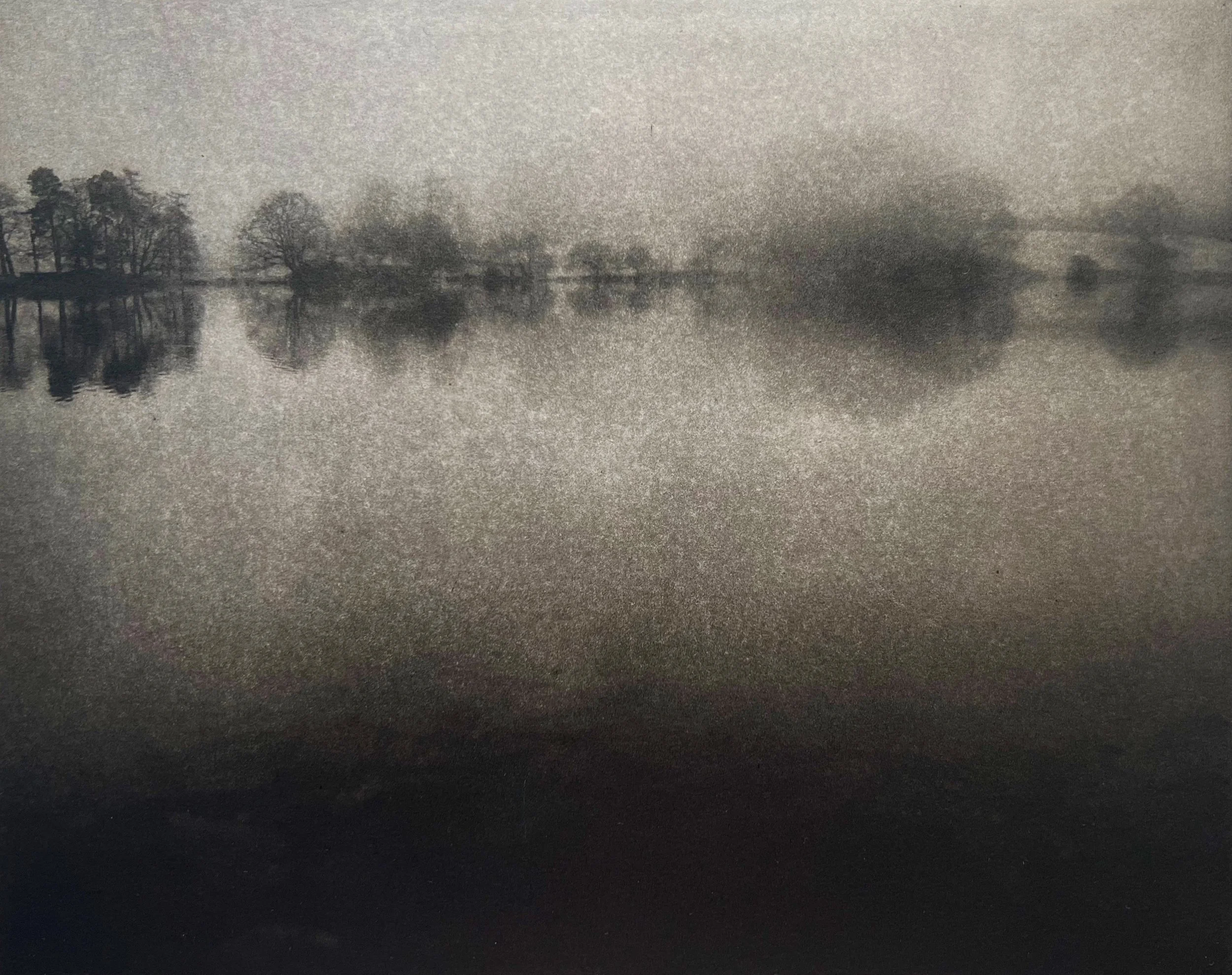

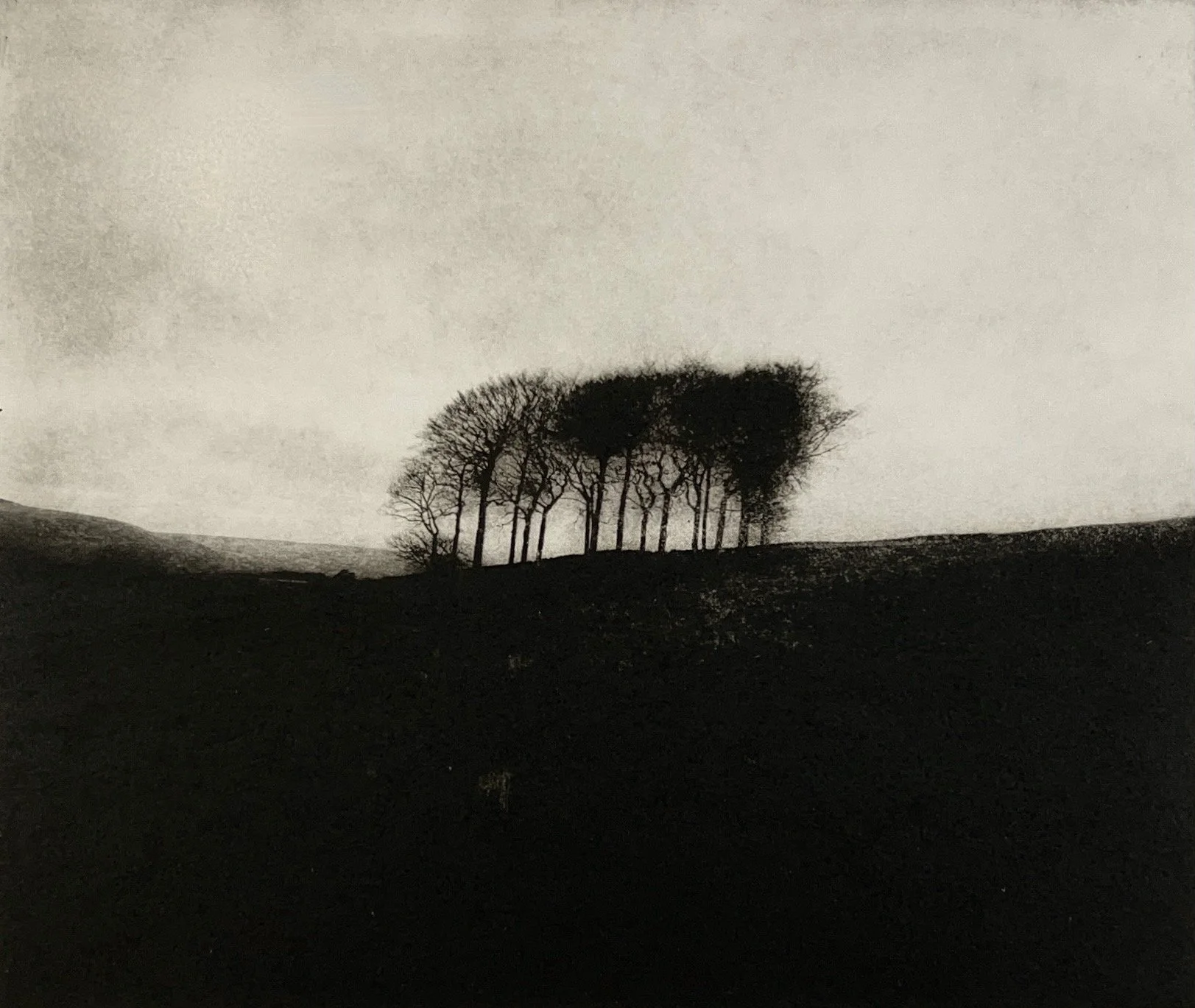

Photogravure doesn’t capture an instant. It captures an atmosphere. The detail is there, yes - but softened, shrouded in ink and texture. Shadows pool. Light drifts. Focus wavers just enough to invite you in.

That whisper of a suggestion is powerful. Because memory, unlike photography, isn’t sharp.

Digital photography offers a timestamp. Photogravure is timeless.

Where the digital image preserves, photogravure transforms. It turns a moment into an object - something physical, layered, imperfect.

The etching process alters the image subtly with each print. No two are exactly alike. It’s as if memory itself is being etched into the paper - not through fidelity, but through interpretation.

We’re not looking at a perfect rendering of what was.

We’re encountering the ghost of it.

Photogravure works the way memory does: slowly, impressionistically, emotionally. It strips away the extraneous, sharpening nothing but sensation.

Poetic Uncertainty: Feeling Your Way Through the Image

It all begins with an idea.

Part of photogravure’s ambiguity, the soft tones, the missing details, lies in what’s left unsaid.

In a world saturated with sharpness, precision, and metadata, photogravure offers a welcome blur. A refusal to define. Its language is one of suggestion rather than statement and in that ambiguity lies its strength.

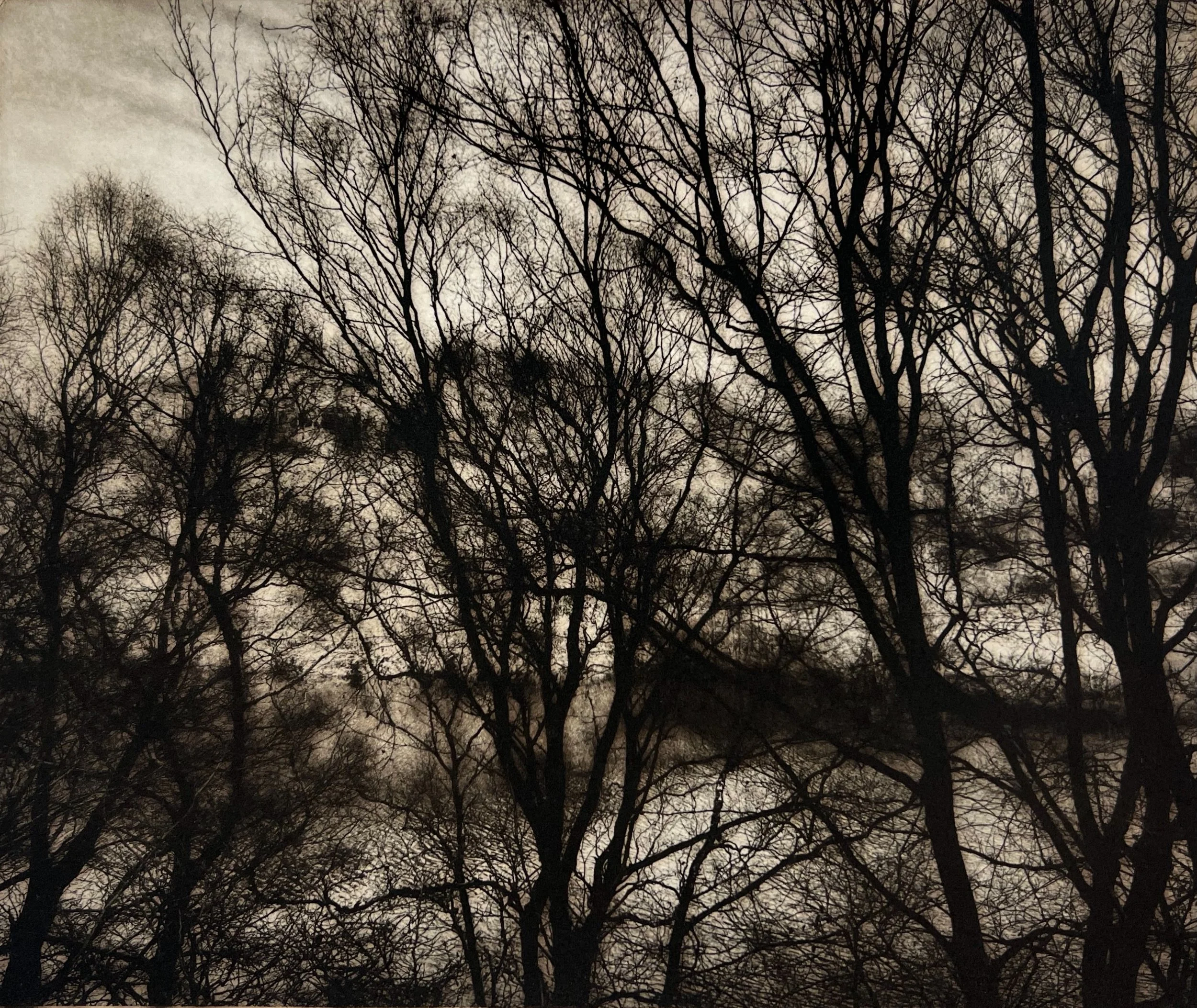

Photogravure doesn’t give us every detail. The soft transitions between light and shadow, the velvety blacks, the texture that seems to shimmer with memory rather than fact - these elements don’t tell a story so much as evoke one. They give the viewer room. Room to wonder. Room to feel.

This ambiguity isn't an accident. It's an integral part of the process. The plate doesn’t record the world like a digital sensor; it interprets it. Ink and paper don’t reproduce exactly—they translate. Something shifts in the alchemy, and that shift creates space. Space for poetry. Space for uncertainty.

The power of the half-seen:

Think of how memory works. We don’t remember life in 300 dpi. We recall gestures, tones, fragments. A hand resting on a window. Light caught in someone’s hair. A glance. These are emotional truths, not factual ones - and photogravure, with its smoky depths and gentle imprecision, speaks in that same emotional register.

Ambiguity lets the viewer participate. Instead of being handed a complete picture, they’re invited to complete it themselves. They fill in the gaps, project their own meanings, feel their way through the image rather than scanning it for data.

It’s an act of co-creation.

There is something deeply human in ambiguity. The need to make sense, the tendency to intuit, the comfort in not having all the answers. Photogravure taps into that. It doesn’t just show - it asks. What do you see? What do you remember? What do you feel?

the ghosts of Stieglitz and DEMACHY

It all begins with an idea.

Thoughts on how a historical process is finding fresh resonance today:

There’s something uncanny about photogravure. It looks like it belongs to another century - because, in a way, it does. The soft focus, the slow process, the rich black ink pressed into paper - it carries the visual and tactile DNA of the early pioneers of the photography, of the mid 19th century and early 20th century. But lately, it’s been showing up with surprising relevance in contemporary practice. In this year’s RA Summer Exhibition, I counted at least 20 artworks that had ‘photogravure’ in their description that had a visual link to a photographic image in their inception.

In a culture of hyper-efficiency and constant digital churn, photogravure offers a deliberate slowness. Its antique qualities are no longer signs of obsolescence, but signals of care. Of choice. Of presence. The process that once symbolised modernity in the hands of a Pictorialist like Robert Demachy or Alfred Stieglitz, the founder of the Photo-Secession movement, now feels like an act of resistance - against disposability, against perfection, against speed.

This isn’t nostalgia for nostalgia’s sake. Photogravure has its roots in the past but it isn’t stuck in it. The look may recall vintage prints, but the hands guiding it are asking new questions. Today’s artists are using photogravure not to mimic history, but to reframe it - to draw out deeper emotional currents, to ground modern imagery in tactile memory, to slow the viewer down.

And it works. There’s something about that etched plate, that soaked paper, that inky impression - it doesn’t just reference the past. It holds it. You can feel time in it.

When a contemporary image - say, a blurred cityscape or a fragmented portrait - meets this historical process, a kind of quiet dissonance happens. The subject says now. The surface says then. And that tension speaks volumes. It turns the image into something reflective, even elegiac. Not quite memory. Not quite moment. Something in-between.

This is where photogravure thrives - in the gap between eras, between technologies, between touch and image. A medium born of invention, reclaimed as meditation.

The Timelessness of Photogravure

It all begins with an idea.

Forget the timestamp - photogravure unhooks us from linear time. It elevates images from moments in time to an artwork.

We live in a world ruled by the clock. Photos are date-stamped, geotagged, time-coded down to the millisecond. Digital photography, for all its ease and precision, often feels tethered to a timeline - evidence of a specific moment, locked into history.

Photogravure, by contrast, unmoors itself from time. It doesn’t tell you when something happened. Its soft edges, deep blacks, and tonal textures seem to say that this is not about time. It’s about presence. Feeling. Echo.

When you hold a photogravure, it doesn’t feel like a record. It feels like an object. The image is not floating on a screen or behind glass - it’s embedded, sunken into the paper, the plate, the ink. This physicality gives it weight - literally and metaphorically.

And with that weight comes a sense of timelessness.

There’s a hush to a photogravure. A softness that avoids precision. The kind of silence that doesn’t explain - it invites. The result is an atmosphere. The subject - whether a face, a landscape, or a shadow - emerges from a place beyond the present.

This ambiguity opens the door to a narrative. Not a factual narrative, but something deeper. Something closer to dream, folklore, or collective memory. When the image is unanchored in time, it becomes archetypal - part of a larger story we all recognize but can’t quite name.

The Art of Seeing Differently

It all begins with an idea.

To view a photogravure is to be drawn in—not just visually, but emotionally.

The image doesn’t demand attention with sharp lines or defined tones - it waits. It waits for the viewer to slow down, to lean in, to let the noise fall away. Photogravure is not made for scrolling; it’s made for sensing. To lingering with. For seeing differently.

In an age defined by instant capture and faster consumption, photogravure reorients us. It’s not simply about looking - it’s about feeling your way through the visual. The soft blacks and velvet shadows, the ghosted midtones, the subtle bite of ink into paper - all invite a different kind of perception. One that resists speed. One that rewards attention.

Photogravure doesn’t offer the pixel-perfect sharpness we’ve come to expect. Instead, it offers atmosphere. Presence.

Where digital images often prioritize clarity, photogravure prioritizes character. There’s a sensuality to the ink, a tactility to the surface.

This is clarity not of detail, but of feeling.

The experience of photogravure isn’t purely optical - it’s physical. The paper holds weight. The plate leaves an impression. Light moves across tones

Before you name what you’re seeing, you’ve already felt it.

You’re not a passive viewer; you’re a participant in the image’s unfolding.

You bring yourself to it - your memories, your questions, your sensations.

Photogravure asks for your presence. Not just your attention. Your willingness to not know everything at once. It rewards the kind of seeing that takes time.

In this, it teaches us something larger about perception: when we train our eyes to slow down, to seek out nuance, to notice the weight of shadow or the space between things - we begin to move through the world more attentively.